News

To Support Local Culture Is to Support Sovereignty (Part 1)

In Caribbean island states shaped by centuries of extraction, spectacle, and displacement, calls to “support local culture” are often mentioned with good intentions but little depth. At worst, they’re gestures: buying handcrafted items, attending a festival, tasting the local food. Yet when considered through the frameworks offered by Antonio Benítez-Rojo in “The Repeating Island” and the exhibition “Tropical Is Political: Caribbean Art Under the Visitor Economy Regime”, this idea of support reveals itself as a far more radical and necessary undertaking that requires political awareness, economic justice, and a commitment to cultural autonomy that challenges both tourism and neocolonial power.

Benítez-Rojo describes the Caribbean not as a unified region but as a “meta archipelago,” a complex, ever-repeating cultural system marked by chaos, hybridity, and rhythm. In this vision, the islands are not isolated or homogenous but linked by shared legacies of violence, invention, and resistance. Repetition in this context does not mean sameness. It refers to recurring cultural patterns, such as rituals, sounds, and gestures, that span geography and time, adapting with each iteration. To support local culture, then, is to recognize this nonlinear, layered identity and resist the temptation to flatten it into a marketable aesthetic.

Culture is not an artifact but a process: alive, unfinished, and defiant.

The exhibition “Tropical Is Political: Art Under The Visitor Economy Regime (circa 2022)” deepens this argument by exposing the machinisms of the visitor economy, a system that transforms island life into a consumable paradise for outsiders. Artists like Joiri Minaya, Abigail Hadeed, and Donna Conlon reveal how tourism, offshore finance, and the legacy of plantation economies continue to shape Caribbean existence. Local culture, in this context, is curated for the foreign gaze, stripped of its history, conflict, and complexity. Support under this system becomes another form of control, where culture is tolerated only when profitable or picturesque.

To truly support local culture, then, is to dismantle these logics. It means honoring the cultural labor of those who remain unseen in glossy brochures: the performers, the stewards of land, the storytellers, the painters and poets whose work resists erasure.

It involves funding the institutions, exhibitions, and publications that give voice to local artists on their own terms, not mediated by foreign curators or economic incentives. It is a stance that recognizes that cultural identity is not just inherited but continually made through struggle and creativity.

Supporting local culture also demands engagement with material conditions such as land ownership, labor rights, and access to education and technology etc. One cannot claim to value the music of a place while ignoring the musician. Nor can one celebrate indigenous food while the land itself is being privatized or poisoned. As “Tropical Is Political” illustrates, cultural support is inseparable from political and environmental sovereignty.

To support local culture is to allow space for ambiguity, contradiction, and critique.

In Benítez-Rojo’s framework, culture is not a neatly packaged story but a polyrhythmic performance: ritual, rupture, and reassembly. It should not be smoothed to fit tourism slogans or state-sponsored branding. True support means allowing culture to breathe, to protest, to evolve without needing to explain or entertain.

In totality, supporting the local culture of an island state is not a passive or symbolic act. It is a commitment to justice, autonomy, and complexity. It means resisting the forces that reduce identity to spectacle and reclaiming the right to define selfhood beyond the gaze of the visitor. It asks us not just to admire the island, but to listen to its repetitions, the sounds of resistance and the whispers of memory.

It is a political, economic, and ethical commitment not a marketing tactic.

To Support Local Culture Is to Support Sovereignty (Part 2)

When corporate gestures toward “local inclusion” collapse under scrutiny, the consequences reach beyond one artist or institution. They reveal the fault lines in a broader system where culture is treated as décor, heritage as commodity, and artists as branding assets rather than agents of meaning.

Recently, I encountered this reality firsthand when a recognized international brand illustrated this contradiction with uncomfortable clarity. Here, a brand invoking “authentic local connection” simultaneously reproduced the very hierarchies it claimed to transcend. My artwork, “Communion,” a meditation on belonging, ancestry, and the sacred relationship between body and land, was appropriated without consent, reproduced in marketing mockups as a staging asset to sell luxury condominiums valued in the millions, and further dismissed when the evidence was presented. The irony was almost theatrical: a work born within the concept of reclamation and memory re-circulated within a system built on erasure and capitalist dreams.

This is not an isolated incident. It is a symptom of the visitor-economy regime that Tropical Is Political warned against; an economy that extracts not only from our landscapes but from our imaginations. When developers or brands selectively include “local culture” in their marketing, they do not nurture it; they instrumentalize it. They convert art into ambiance, history into wallpaper, and the artist into a ghost.

To support local culture, therefore, is to demand accountability when that culture is misused. It is to insist that creative labor be respected with the same gravity as material property. It is to question the power structures that decide who gets to represent “the Caribbean,” and under what terms. Sovereignty, in this sense, is not merely political independence; it is epistemic, aesthetic, and moral. It is the right to author one’s own image.

But this interrogation cannot stop at institutions or developers; it must also extend to those who buy into these visions. How many purchasers of luxury properties or branded experiences in small island states ever question the cultural and ethical costs of what they consume? How many are aware that their investments may indirectly fund the exploitation or exclusion of local creative communities, the very communities whose culture they are promised as “authentic experience”?

This question is not rhetorical; it is structural. Every image, every motif, every marketed sense of belonging carries an origin. Behind the seamless marketing lies an ecosystem of creative labor; often unpaid, uncredited, or replaced. When culture is commodified, the consumer becomes part of that cycle, whether knowingly or not.

The above example exposes the fragility of cultural agency within the global hospitality complex, but it also affirms the resilience of artists who refuse to be silent. The act of reclaiming one’s work, of naming the injustice publicly, is itself an act of cultural resistance. It says: our art is not for decorative consent; our stories are not set pieces in someone else’s paradise.

To support local culture, then, must go beyond patronage or PR. It must involve structural change; legal protections for artists, transparent inclusion policies, and the creation of institutions owned and led by local practitioners. It must mean confronting the uncomfortable truth that “luxury” in the Caribbean has too often been built on cultural dispossession.

Supporting local culture is not charity. It is reparative justice.

To stand for culture is to stand for sovereignty, not only the sovereignty of land, but of voice, image, and imagination. And in that struggle, every artist’s refusal becomes a seed: a declaration that the Caribbean, The Turks and Caicos, is not a backdrop, but a beating, remembering, and self-defining world.

UP & AWAY

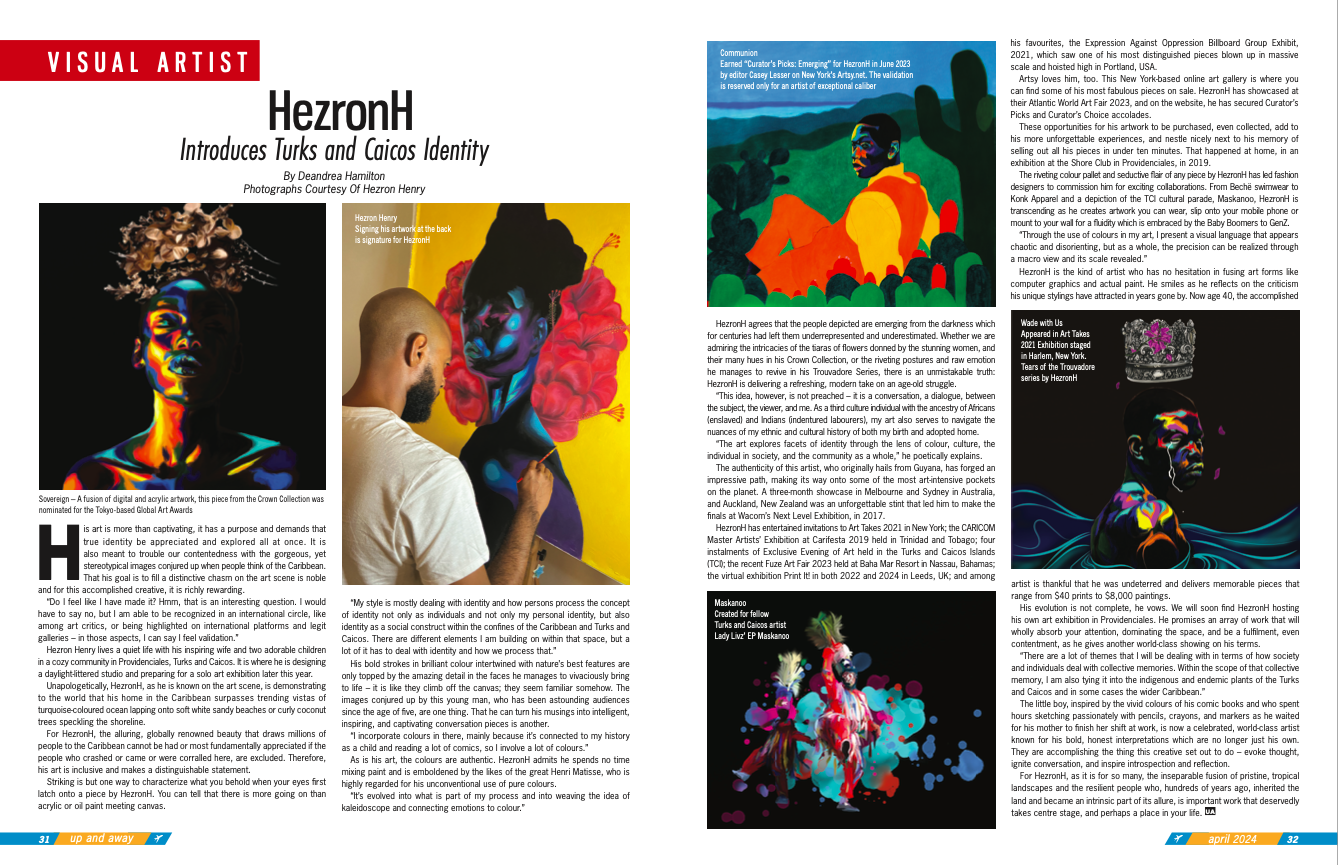

Pick up the recent issue of Bahamas Air In-Flight Magazine for an exclusive interview!

Up and Away: Bahamas Air In-Flight Magazine Apr - Jun 2024